Apr 8, 2025

By Michael L. Kasavana, Ph.D., CHTP, CFTP, MSU Professor Emeritus, AHLEI Author

The Power of Menu Engineering - Part One

Part One: Introduction

Perhaps the oldest misconception in food service management is that food cost is directly related to profitability. In other words, it is assumed that the lower an operation's food cost percentage (food cost divided by food revenue), the more profitable the restaurant. Unfortunately, this is not always the case. Alternatively, the menu engineering model (ME) requires management to focus on the dollar amount a menu item contributes to profitability as opposed to simply monitoring its food cost calculation. Despite the fact that it has been more than four decades since the concept of menu engineering was introduced to the food service industry, a recent Google Chrome search revealed 2.96 billion, not million, results demonstrating the longevity and relevancy of the approach.

Menu engineering is used to enhance profitability and customer satisfaction. Menu engineering examines the impact of menu item descriptions and placement on profitability and popularity. While the goal of menu engineering is to increase customer visits and spending per visit, industry practitioners point to the involvement of marketing, psychology, and graphic design as important components. It the resulting outcome of pricing, design, placement, and content that differentiates competing menu items against overall menu performance. Instead of concentrating on: “What is a satisfactory food cost percentage?" menu engineering is concerned with, "Is the restaurant receiving a reasonable contribution to profit given its menu mix?"

ME analysis goes beyond traditional restaurant metrics by assisting operators in obtaining a reasonable level of profitability through increased customer demand and/or average contribution margins. While most foodservice analytical applications primarily focus on controlling percentages, menu engineering deals with enhanced decision-making strategies related to customer preferences, promotions, and pricing. A menu engineering analysis centers on three basic data elements: a) customer demand (number of covers sold), b) menu mix (sales preference scoring), and c) contribution margin (gross profit tabulation). ME provides both an item and overall comprehensive investigation of competing menu items, by meal period, while establishing a dynamic standard against which future menu changes can be measured.

Background

According to numerous authoritative web resources, the term ‘menu engineering’ refers to a specific restaurant menu analysis initially developed by Michael L. Kasavana and Donald I. Smith at the Michigan State University School of Hospitality Business (circa 1982). Kasavana and Smith developed the analysis with the objective of encouraging restaurant customers to purchase targeted menu items, presumably the more profitable items, while discouraging the purchase of lower profit items. To that end, operators need to first calculate the direct cost of each menu item. This costing exercise extends to all items listed on a menu and should reflect all expenses incurred to produce and serve an item. Optimally item costs should include food cost (including wasted product plus product loss), incremental labor (cost of in-house preparation, production and plating), condiments, and packaging, if any.

Historically, restaurant managers have relied on two criteria for determining the items to be featured on a menu: 1-lowest food cost percentage and 2-highest number of items sold. The percentage of food cost is calculated by dividing the total cost of the menu item’s ingredients (including garnishes and side items) by the menu item’s selling price. The number of items sold equals the total sales of each item purchased during a meal period. Advocates of menu engineering counter this approach by focusing on gross profit (contribution margin) and menu mix (sales). Believing that gross profit trumps food cost, menu engineering deals with the identification and promotion of menu items with the highest gross profit, not lowest food cost.

A frequent and complex issue with this approach is that items that are highest in gross profit typically are higher priced menu items that almost always fall within the higher end of the food cost percentage scale. Operators who believe that a low food cost percentage is more important than gross profit tend to promote menu items carrying a lower food cost percentage. Unfortunately, these items are typically the lower priced items on a menu and correspondingly are lowest in contribution margin. Therefore, promoting low food cost items often results in a lower average check and lower gross profit. It is, however, important to note that low food cost and high gross profit are not mutually exclusive. It is interesting to note, however, the percentage of restaurants that self-report using menu engineering totals around forty percent as depicted in the following pie chart.

While there is simply no single method of analysis that can appropriately address all varieties of menus across the industry, the power of menu engineering has been proven successful. For example, if a menu item perceived as a "commodity" like hamburgers, chicken tenders, fajitas, and other items found on many restaurant menus, pricing will tend to be somewhat restricted and more moderate. Should a proprietary menu item be considered a "signature” or “specialty" selection unique to a particular restaurant, pricing may be more flexible and tend to be higher than average. These examples help illustrate the potential complexity, and impact, of menu item price elasticity.

Contribution Margin

After a menu item's cost and selling price have been determined, analysis and evaluation of an item's profitability is based on the item's contribution margin. The contribution margin is calculated as the menu price minus the item’s direct cost. Menu engineering then focuses on maximizing the contribution margin across the menu. Recipe costing needs to be updated and verified whenever the menu is re-engineered.

In general, the term menu engineering is used within the foodservice industry but can be applied to any industry that displays a list of competing products or services. Typically, the goal with menu engineering is to maximize a restaurant's profitability by subconsciously encouraging customers to buy what management wants them to buy and discouraging purchase of other items. Fields of study which can contribute significantly to menu engineering include:

- Psychology (perception, attention, and emotion)

- Managerial accounting (contribution margin and unit cost analysis)

- Marketing and strategy (pricing, placement, and promotion)

- Graphic design (layout, gaze motion, and typography)

By analyzing a menu to identify high-profit items and potential promotional campaigns, as well as rotating seasonal items, will help the menu stay fresh and engaging. Also, upselling and cross-selling techniques can be highly effective.

The ME Process

The downloadable booklet entitled “Menu Engineering Bootcamp” from industry leading supplier Toast, includes a series of lessons designed to increase restaurant profitability in thirty days or less. The five lessons are:

Lesson 1. An investigation of the menu

- cost of goods sold

- menu item food costs

- food cost percentage

- contribution margin

- menu item popularity

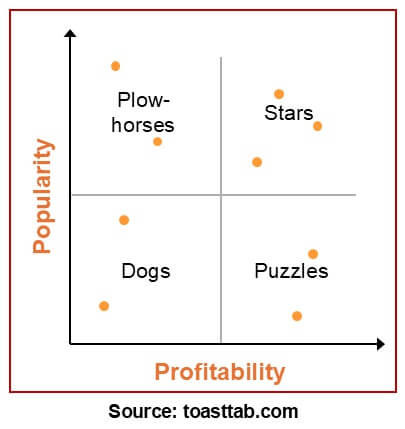

Lesson 2. Classification of Stars, Puzzles, Plowhorses, and Dogs

- Stars – high profitability and high popularity

- Plowhorse – low profitability and high popularity

- Puzzles – high profitability and low popularity

- Dogs – low profitability and low popularity

Lesson 3. Determine menu item characteristics

- Paradox of Choice – avoid too many selections

- Decoy Effect – be aware of price-sensitivity

- Social Proof – the ‘me too’ review effect

- Semantic Salience – noticeability of symbols

- Eye Movement Patterns – menu design

- Descriptive Language Labels – yield expectations

Lesson 4. Avoid common menu item gaffes

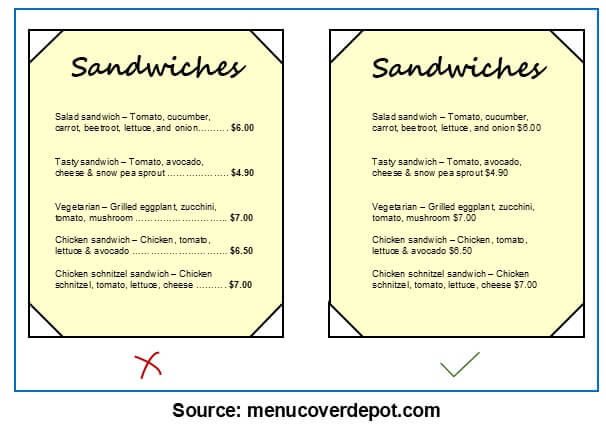

- Readability – don’t make the menu hard to read

- Layout Effectiveness – don’t misuse spacing

- Visualization – don’t forget about featured branding

- Sizing – don’t size menu too large

- Choices – don’t overload menu with too many items

- Subtlety – don’t oversell your menu items

- Layout – don’t be too bold with menu organization

- Upsell – don’t ignore upsell opportunities

- Quality – don’t print a flimsy menu

- Copywriting – don’t write unappealing descriptions

Lesson 5. Explore menu item adjustments

- Menu Revisions – done twice per year

- Change – menu items and menu design

- Tracking – quarterly analysis of effectiveness

- Compare – menu engineering spreadsheets

The website menucoverdepot.com emphasizes the following menu design techniques:

- Space requirements – highlighting items often takes up additional menu space, so don’t make the mistake by choosing a menu layout that doesn’t provide enough room to effectively promote profitable menu items.

- Pricing options – placing menu item prices in a column causes customers to focus on price, not food, and may lead them to choose the cheapest item in the column.

- Frequency – when increasing the number of items on a menu, consider using visual cues to break up listings. Cues can have a positive bottom-line impact so long as the menu is not needlessly cluttered (one highlighted item per category).

- Photographs – while not appropriate for all operations, research indicates that strategic use of high-quality photos can increase item sales by as much as 30%. Limiting the number of photos helps ensure a reasonably balanced presentation.

It is important to note that visual perception is inextricably linked to how customers read/peruse a physical or digital menu. Most menus are presented visually (though many restaurants may verbally add daily specials) and the majority of menu engineering recommendations focus on how to increase attention by strategically arranging menu categories. This strategic placement of categories is often referred to as the ‘theory of sweet spots.’ The thought being that customers are most likely to remember the first and last things they see on a menu; hence, these are referred to as its sweet spots.

By Michael L. Kasavana, Ph.D., CHTP, CFTP, MSU Professor, Emeritus, AHLEI Author of the Eleventh Edition of Managing Front Office Operations.